Calling Buckminster 4! A Telephonic History of Flatbush

“A new year now means a new world,” proclaimed the New York Standard Tribune on January 1, 1880. “For centuries science crept; then it marched, then it ran, now it flies on the wings of the lightning.” The technology that was flying on lightning’s wings was telephones, which had just begun to be installed in New York. That year, the first telephone numbers were issued in the city, which you would use by picking up the phone and telling to an operator — but it was still common practice to simply name a business or (rich) person.

The first telephone in Flatbush was installed in Hendrick Van Kirk’s general store, according to Van Kirk’s son (Henrick, Jr) in the book Tales of Old Flatbush. He describes the phone as “a rubber terminal with a whistle at the end of a speaking tube that extended to the second floor.” He also recounts what he believes to be the first telephone call in history made from Flatbush — his father calling a store in Downtown Brooklyn to check the competitor’s price of a plow. Whether just before or just after the advent of phone numbers, the elder Van Kirk didn’t use them. Jr writes that his father “first blew the whistle and then demanded, ‘I want to talk to Mr. Vanderbilt of Vanderbilt Bros., 23 Fulton Street, New York.’” He was able to double-check that his competitor was selling the plow at a similar price, contrary to what a customer (trying to bargain) was telling him.

The oldest phone numbers in New York had 2 or 3 digits, but soon, they all had 4, preceded (or followed) by the name of the exchange. If you were calling someone in Flatbush, you’d pick up the phone and say, for instance, “Flatbush 9234, please.” At first, exchanges were literally buildings full of switches staffed by people plugging and unplugging wires like you see in old movies, and were a huge new source of needed labor, especially in large office buildings (in the 1890s, Manhattan needed one switchboard operator for every nine people because of the huge volume of calls). Young, unmarried white women suddenly found that older white men were willing to hire them for these low-level positions — since the job hadn’t existed before, it didn’t feel like they were taking it away from a man. Later, as technology advanced, these women were able to transition into other office roles, like typists.

Meanwhile, phones became more automated, with exciting new rotary dial technology. (Many of us are old enough to remember our parents’ or grandparents’ rotary phones.) Phone numbers changed to consist of 2 letters followed by 5 numbers, but all the letters corresponded to a number on the dial: 2 = A, B, or C; 3 = D, E, or F, and so forth. So “Flatbush 2-4923” would be spoken as such, but dialed as FL2-4923, or 352-4923. At first, the exchange names often corresponded to a place name. But later, words were chosen almost at random to correspond with new phone numbers (literally it was just a dude at the phone company making sh*t up). For instance, many Flatbush numbers were on the “Buckminster” or BU exchange, which meant…nothing, except that they started with a 2 and an 8.

Flatbush exchanges included:

BUckminster

CLoverdale

DIckens

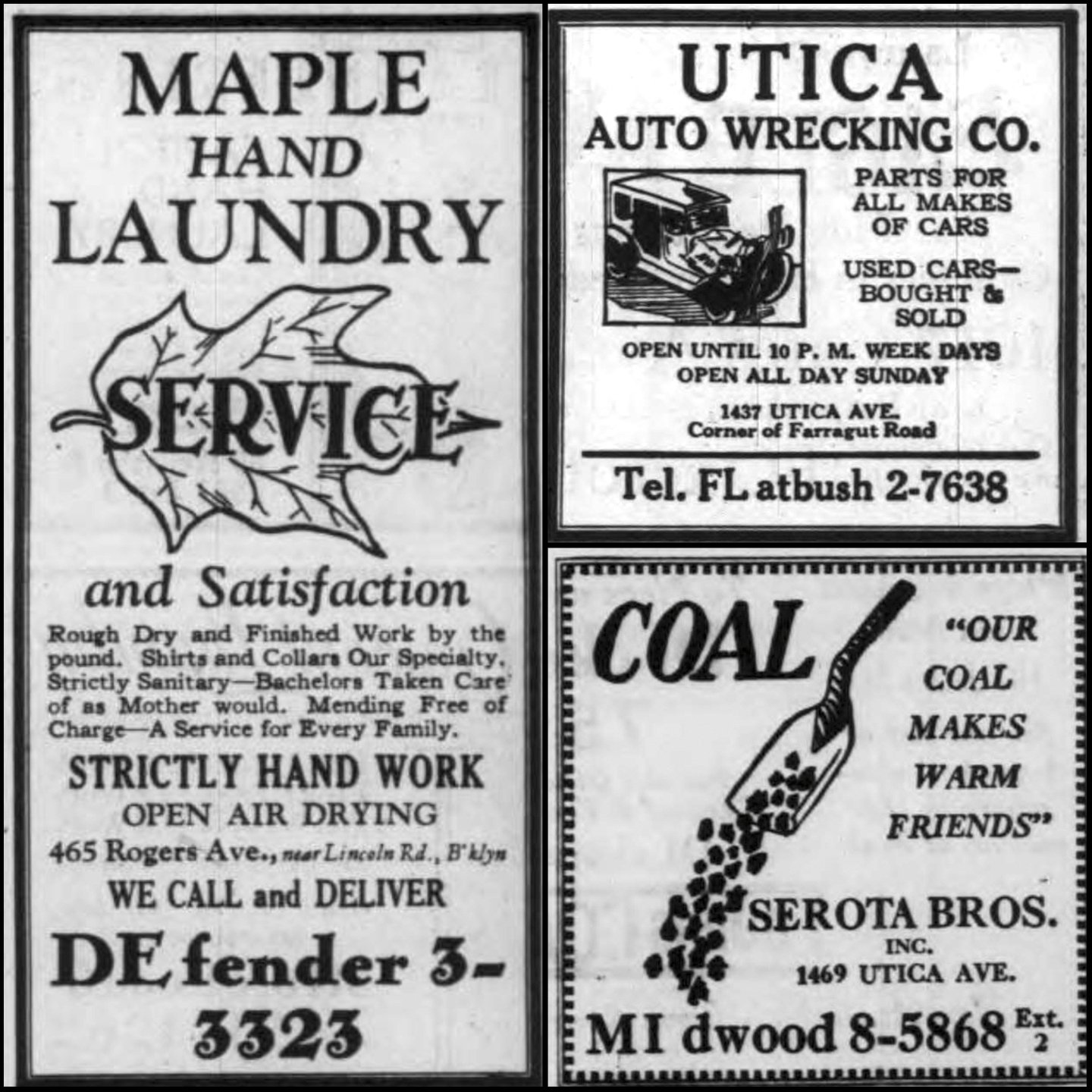

DEfender (or DEwey)

ESplanade

GEdney

FLatbush

INgersol (or INgersall)

MAnsfield

NIghtingale

ULster

WIndsor

Wouldn't it have been so cool to tell someone your number was “Cloverdale 5, 5348” or “Nightingale 2, 8469” (especially in a Mid-Atlantic accent)? New Yorkers seemed to think so, and we especially loved the status that various exchange names provided, since they denoted roughly what neighborhood we lived in or how long we’d been in the city (similar to having a 917 or 718 area code today). That status can be seen in the 1941 film Ziegfeld Girl starring Jimmy Stewart and Lana Turner as sweethearts from Flatbush. When Lana gets an opportunity to star in a Ziegfeld show, the talent scout mentions changing her last name for show business. Then he asks her phone number.

“Flatbush 7-098,” Jimmy says. “I suppose Mr. Ziegfeld can change that too, huh?”

“Yes,” the scout answers, drolly listing the exchange for the Upper East Side: “To Butterfield.” (Butterfield 8 would later become a famous 1960 movie starring Elizabeth Taylor as a socialite.)

New Yorkers loved the cache of our exchange names so much that we kept them as part of our phone numbers for longer than any other city in the US. “No longer, says the New York Telephone Company, will we be able to drop BUtterfield 8 or RHinelander 4 or PLaza 5 exchanges at parties and expect appreciative stares,” lamented a New York Times writer in 1978 when letters were finally dropped from the NYC phone book — long after they were gone everywhere else (98 percent of the country just used numbers). “Are no vestiges of status to be left to us?...Who will know where 286, 632, 744, 755, 737, or 838 are?”

And so, CLoverdale 5-5348 became 255-5348 for good. And pretty soon, the 718 area code got tacked onto the front. But believe it or not, you can still see traces of the old exchanges in some of the oldest businesses and organizations of Flatbush (and perhaps if you know someone who still has a landline). In fact, the 63rd police precinct, Ideal Uniforms on Flatbush Ave, and Di Fara Pizza all have Cloverdale numbers: numbers that begin in “25.” The Dutch Reformed Church, Holy Cross, Scoops (vegan restaurant) and Cookies (kids clothes) on Flatbush, and Das Upholstery on Cortelyou all have Buckminster or “28” numbers. The Makki Masjid Muslim Community Center on Coney Island Ave has an old Ulster number (85), while the Junction YMCA, St. Paul’s Methodist Church, and PS 181 all have Ingersoll (46) numbers. Got any more to share? If you grew up in Flatbush and had a phone number with an exchange name, what was it?

An early phone adopter, Printer Edward E. A. Fritz on Flatbush Ave got a 4-digit phone number: Flatbush 1670. This ad, placed in the 1907 Erasmus Hall yearbook, even features cute lil’ phone illustrations.

One of the first businesses in Flatbush to have a phone (as early as 1899), real estate agent John Reis had a 2-digit phone number, Flatbush 55.

A candlestick-style phone is modeled in this 1925 article from New Republic magazine that made fun of dating over the phone.

Flatbush phone exchanges from the 1931 Brooklyn phone book, including FLatbush, DEfender, and MIdwood.

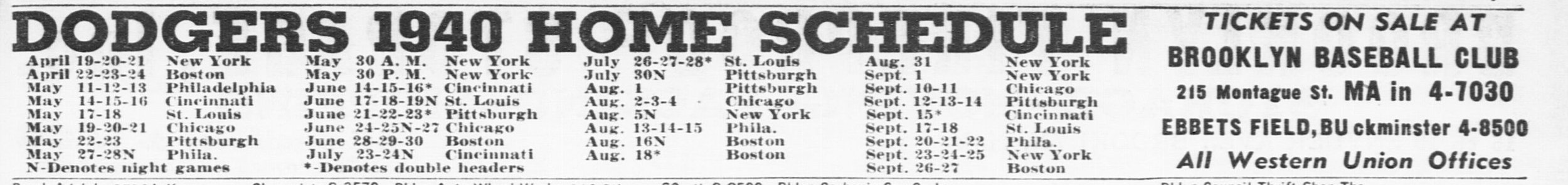

BUckminster 4-8500 (see far right) was the phone number for Ebbets Field, the home of the Dodgers.

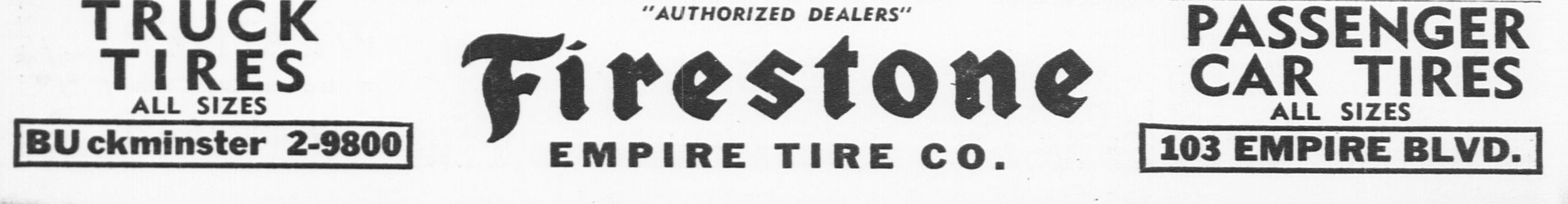

The Firestone at the corner of Empire Blvd and Bedford, next to Dodgers Stadium (demolished in 2023), also had a BUckmister telephone exchange.

Jimmy Stewart reps the Flatbush phone exchange in 1941’s Ziegfeld Girl

This employment ad from the NY Telephone Company seeks “Girls 16 years and over” to work switchboards throughout Brooklyn, including in Flatbush.

A 1940s Flatbush Ave Upholstery Store with an A+ name and BUckminster phone exchange.

Written in 2023/2024 using the following sources:

The Telephone EXchange Name Project

Tales of Old Flatbush by John Snyder, 1945

Ephemeral New York (Two-letter phone exchanges and More old-school phone exchanges)

When Did NYC Lose Its Iconic Letter Telephone Exchanges?, The New-York Historical Society

The New York Times (PHone EXchanges LOse THeir LEtters, 1978; Dialing Up History, 2008)

Analog City: NYC B.C. (Before Computers) - exhibit at Museum of the City of New York, 2022

Old phone directories from the Brooklyn Collection and NYPL Collection

1940s.nyc

Want to do your own Flatbush research? Visit the Flatbush History resources guide

A rare photo of the short-lived Cortelyou Rd trolley.